The earth belongs to the Divine

and everything on it.

For the Divine wove it out of the emptiness of space

and breathed life into every corner,

bringing forth all life,

and all of it precious.

Who is fit to care for this

and worthy to act as God's representative?

Those passionate for truth,

who are horrified by injustice,

who stand with the poor,

and take up the cause of the helpless.

Those who let go of selfishness,

and see the sacred hoop of the world,

refusing exploitation of any creature,

or the fouling of her waters and land

Their strength is in compassion.

Divine light shines through their hearts,

and their children's children will be blessed

and bless the world.

Psalm 24 (my paraphrase)

Last week I wrote of my reading sacred texts with “Zen eyes,” my attempt at a nondual hermeneutic that I could apply when reading texts not from the Zen tradition. Here is how I have tried to do this with the Psalms. It was a project that I took up when visiting with an old colleague and former professor who had suffered a devastating series of strokes, where our only heartful way to communicate was my reading to him.

We settled on the Psalms.

The psalms are a wildly diverse selection of ancient near eastern religious poetry. The Psalter, that is the collection of poems taken together, depending on how one counts, either 151 or more commonly 150, reside at the center of much of private and corporate prayer within both Jewish and traditional Christian worship. They’re uneven, to say the least. Ancient war chants, anyone? But the best parts of them are astonishing, subtle, and compelling.

The psalms themselves are, well, I find I keep coming back to that word: ancient. Most scholars believe psalm 90 is likely the oldest, while psalm 29 as a gloss on a much older Caananite hymn is another candidate. Some enthusiasts suggest the oldest of the psalms were written more than three thousand years ago. While that’s in all likelihood quite a stretch; many, possibly most were written before the Babylonian captivity in the sixth century before our common era.

They were compiled as a liturgical document sometime in the Second Temple period. So, somewhere after about 500 years before our common era. They are gathered as the first volume of the third part of the Hebrew Bible, the Ketubim, the “Writings.”

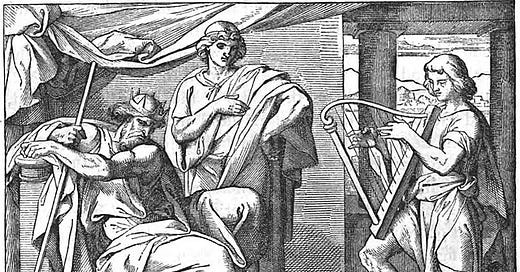

In the King James Version there’s a little trick of it being right in the middle of the book, so it’s easy to find them. The psalms are the longest book of the Bible, consisting entirely of religious poetry. Although the “religion” of some of them is hard to see. Did I mention war chants? Perhaps they all were originally meant to be accompanied by music and many offer some guidance to the appropriate instrument to be played as they were recited or sung.

The collection of the Psalms is traditionally divided into five books, perhaps echoing the Five books of Moses. Contemporary scholarship suggests the first three of these books, Psalms 1-89 are the oldest strata of the collection, that pretty clearly before the Babylonian Captivity part. The balance of the psalms don’t appear to have been settled as part of the canon until the turn into our common era, roughly the time of Jesus.

There are clusters of psalms with related significance. But the only arc most can see in the collection is a general movement from lament to praise. Some psalms are obviously meant for corporate worship, while many seem very intimate and personal. In addition to lament and praise, some are didactic, little sermons. Nearly half the psalms are attributed to the semi-legendary king David.