A couple of years ago I received a message from my colleague and friend, John Buehrens. Among other things he’s the onetime president of the Unitarian Universalist Association. John informed me that one of our colleagues, David Keyes, had suffered a swarm of strokes and was now living in a nursing care facility in Los Angeles. He didn’t need to remind me that David had been one of my professors in seminary. He simply asked if I could visit.

Of course I could. The facility where he was staying was at best a forty-five minute drive from my home along the notorious Interstate 405. Notorious because seemingly at random hours in the day or night the freeway becomes a many miles long parking lot. A bit of a daunting drive and an exercise in not knowing. Still, it was important for me to visit on some kind of regular basis.

Over a while we settled into a weekly visit. This continued for a year until he died. David’s cognitive abilities were only slightly impaired, but his speech was heavily slurred, and he was wheelchair bound. When I first began to visit, I learned any serious conversation was extremely difficult. And quickly from there his speech deteriorated to the point I could only make out an occasional word.

Early on we agreed the visits would mostly be me reading to him. David was a prominent figure in the UU Christian community, a significant if small band maintaining historic connections within a now wildly pluralistic to the point of becoming an essentially non-Christian Religious association. He loved Jesus in his peculiar Unitarian sort of way. It didn’t take long for us to settle into me reading the Psalms to David as the greater part of our visits.

It was a powerful year. We wandered through the entire collection, trying several translations. And then settled into a large handful that I particularly found moving. David seemed to like them. But I suspected he liked physical company mostly. We shared those texts, visiting, and revisiting. I found some deeply moving.

Somewhere along I realized as I read how many made sense of the texts within a nondual context. That is, I could read some passages as if they were Zen wisdom. Others were not so easily met. But nonetheless as a Zen Buddhist reader I found how as a collection they were rich and challenging and worthy.

And before I go any farther, I want to assert something terribly important. The spirit rests where it will. The wisest people are not necessarily the best read. The gifts of depth and wisdom are our common inheritance as human beings. It’s even a trope in spiritual literature to underscore how great sages are often illiterate. I think of Huineng, Zen’s Sixth ancestor. And I think of Mugai Nyodai, better known as the nun Chiyono. Illiterate she worked as servant in the convent. One day while carrying a bucket of water, the bottom of the bucket fell apart. As the water washed over her feet, she had an explosive realization of who she and the world really were. A story that has pointed the way for so many.

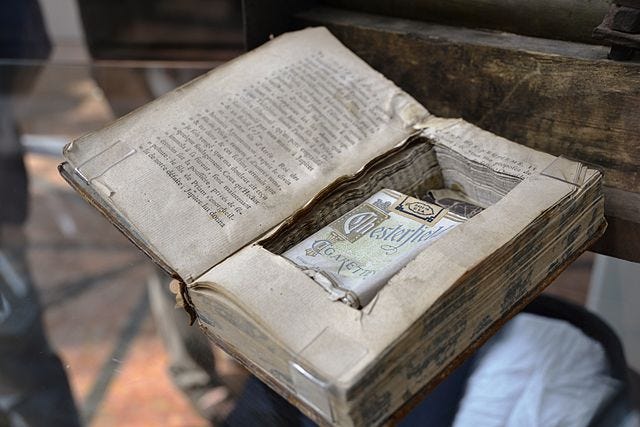

Also, not every text that is presented is worthy. Some turn out to be all pretty on the outside but contain poison of one sort or another inside. Now, this is rarely the case for texts that have been around for a while. The more problematic are the more recent, as general rule. The tests of time tend to weed these things, and what we get from our ancestors is usually a distillation.

What I am thinking about here are those texts, the gifts from the deep. From our own specific traditions, and from the treasure trove of the world’s traditions. We can profit deeply from our engagement with sacred texts. They are the repositories of our ancestor’s wisdom. And understanding how to read them is very important.