(a sermon first delivered at the Santa Paula Universalist Unitarian Church on the 29th of December, 2024)

Go, go, go, said the bird: human kind

Cannot bear very much reality.

Time past and time future

What might have been and what has been

Point to one end, which is always present.

T. S. Eliot “Burnt Norton”

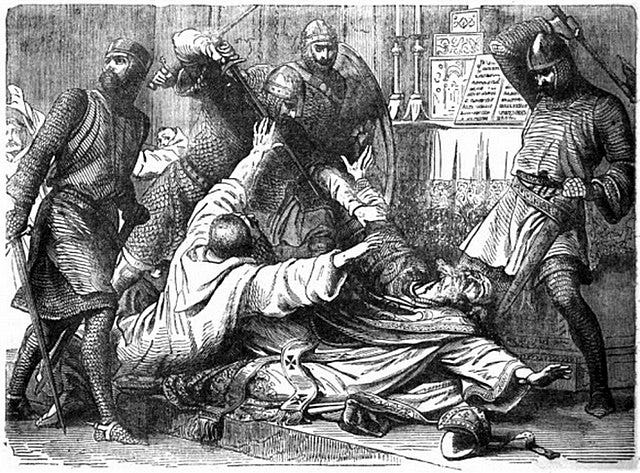

The story goes that on Christmas day in 1170, King Henry II muttered “will no one rid me of the troublesome priest?” In some accounts the priest was meddlesome, in others turbulent. In each case perhaps we can hear an echo of Paul’s letter to the Romans 7:24 "O wretched man that I am! who shall deliver me from the body of this death?"

Much has been made of the fact it was not a direct order. It was possibly just an offhanded remark. Not given to subtly, however, four knights who heard him, Reginald FitzUrse, Hugh de Morville, William de Tracy, and Richard le Breton took his words with the power that words can have and immediately went to Canterbury. There the knights challenged the archbishop. And then they killed him.

The murder took place on the 29th of December. So, 854 years ago, today.

Becket is one of those endlessly fascinating characters. He came from about as far down the social ladder of that time and place as one can and have any chance of advancement. He was educated, but it’s not clear how well. For instance, it appears his Latin was never more than rudimentary. Again, important in that moment.

The main chance came when he entered the household of the then archbishop of Canterbury, Theobald of Bec. The young man proved to have diplomatic skills. And this led him rather quickly to the king. That and apparently enjoying many of the same tastes as the king won him favor. Before long Becket was named Lord Chancellor, sort of the kingdom’s attorney general. He had arrived as a full-on crony to Henry. He was someone who could be trusted to put the king’s desires before anything else. Becket seemed totally unencumbered with scruples. And so when the opening occurred Henry nominated Becket to be the next archbishop of Canterbury.

It was a bit of a rush job. He had to be ordained a priest the day before he was consecrated bishop. What no one foresaw is how seriously he would take his new job. He no longer was the king’s lacky, but God’s. He full on embraced the holy life, even taking to wearing a hair shirt, a mortification embraced only by the most zealous. This shift in allegiances would lead to years of conflict, for a long time of exile, and all in all pretty much on a straight line to that murder.

Me, I was fourteen when the film Becket premiered. I loved it, staring Peter O’Toole as the libertine king and Richard Burton as Becket. I was fascinated with religion and loved the pageantry and the magnetic screen presence of both O’Toole and Burton ever as much as the spiritual question of Becket’s unexpected conversion and what it led to. Memories of the film would linger.

By about eighteen I was now fully consumed with spiritual questions. And I was devouring a variety of texts all circling on my own growing spiritual crisis. The questions for me “Is God real?” and “Who am I?” and “what am I?” and “How should I live meaningfully?” were absorbing, challenging, and mocking. Among the books I found at that time were two of T. S. Eliot’s plays, “the Cocktail Party,” and “Murder in the Cathedral.”

I half remembered the film. This was something of a new category. As a play “Murder” first opened in 1935. It has a small cast. There’s Becket. There’s a Greek Chorus of sorts. There are priests, and of course, there will come those knights. But Becket’s inner life is what it’s all about. Filled with questions that echoed for me my own quest for meaning. The play was not a big commercial success.

What I found especially important, and what I would like to touch on here, is how in the play Becket wrestles with various temptations as he tries to live into his place as the foremost religious leader in England.

I think this is important. Today we find ourselves in such complex and terrible times. There’s that momentous election, just to kick things off. And, well, set the tone of our moment. There are wars and rumors of wars, an ever present haunting for the heart. But for us specifically, we have so many domestic issues presenting. Women’s rights are on the line. As are the rights of the LGBTQ communities. There is the plight of the poor, always the poor. Immigrants are facing a terrible backlash. And the earth itself is groaning under the weight of human action. To start the list.

The question here as a new year dawns is how do we meet all this? For me this is actually a spiritual question. A spiritual question with immediate practical consequences. With that Eliot’s presentation of Becket’s temptations are ours. At least if we agree this is all ultimately about the heart, about who we are, and how we are to meet this world.

With that the temptations. The first turns on our physical safety. The second considers the rewards of simple submission to what’s happening. The third is how we choose to engage the matters in front of us.

The fourth temptation is maybe the most complicated. For Becket it was to embrace his martyrdom. This appears to be the great challenge for him, at least in Eliot’s telling. There’s a lot of pride in that embrace. Eliot sings for us his awareness: “The last temptation is the greatest treason:/To do the right deed for the wrong reason.”

And so for us the question is what are we really doing as we meet the world in its suffering.

At the point dividing the first part of the play from the second there’s Becket’s Christmas sermon. The sermon blending, as the holiday does, rejoicing for a newborn and all that hope with a constant foreshadowing of death and mourning. Kind of like life itself, when we really look at it. It provides a suitable tone for things of the deepest importance.

For me the play invited a sense of embracing the whole mystery of existence as it unfolds, both what has been, and what is to be. With it, for me, at that time also reading the Bhagavad Gita. I found within the weaving of the cosmic fabric, a sense of some larger destiny. Heady stuff for that cusp between adolescence and young adulthood. For me it was the stuff that would lead me into a Zen monastery.

And you know. It still works. It feels especially right for our moment, this one, today, and tomorrow as we look toward the new year.

The second part of the play barely mattered to me. I even had to look it up to recall what was what. The confrontation between Becket and the knights embarked on their terrible quest. Explorations of justification of several sorts. The murder itself. And then the knights protesting their moral innocence.

What will be, will be. And maybe there’s a deeper point. Our effort is at the front end. How do we meet things. After that it’s no longer in our hands. And it is probably wise to let go of that part.

For me the questions are how do we meet the moment? How do we be true to our deepest calling, the knowing of our hearts? And with that acting with intention, grace, some humility, and for the genuine good. For ourselves, for those around us, and for this holy ground upon which we stand?

Here I think of that term troublesome priest.

I think of the late congressman John Lewis and his call to good trouble. How do we live faithful in these hard times? How do we become troublesome priests, in that good trouble sense? Worthy of the moment. Worthy of each other?

Here I find Becket’s temptations, okay, Eliot’s show a way.

First there’s one’s physical safety. Really the passive voice isn’t quite right. This is about my physical safety. It’s about your physical safety. Taking care of ourselves, and by an easy extension, caring for those we are closest to. This obligation feels so true, to the bones true. In fact, it’s biological. We need to attend to this.

However, there’s something more complicated in all this. I think of the golden rule the universal, or near enough, ground for all human ethics. I find its phrasing in Jesus’ second great commandment, to love our neighbor as ourselves hints at a deeper truth.

Here’s the spiritual mystery. Where is the real line between self and other, after all? The edge of our skin doesn’t seem to hold up when we think about how we really are formed as human beings. And with that the consequences in other lives with every choice we, you and I make. With every action we, you and I take.

So as far as physical safety is concerned it’s complicated. It doesn’t lend itself to a simple I’ll care for me and mine. The rest of you, you’re on your own. Not if we’re being brutally honest with our hearts. Not if we’re open to the mysteries of love.

The second temptation is to bow to authority even if it is an unjust authority. You know, go with the flow. Frankly, it’s easy enough to do - if you’re not the target of unjust authority. And, as pastor Martin Niemöller warned us “first they came for the socialists...” And it ended with himself, alone in a Nazi prison camp.

Back to the wild interdependence.

The third temptation is bound up with our joining organized opposition to authority, especially corrupt authority. This is not the temptation. To do something like this can be very important. But there’s a subtle danger that we need to be aware of. We can be so caught up in party or ideology that we miss the most important things. Which, to repeat, is the truth of our radical interdependence. The power of love is our unbreakable connection to each other. And this is the radical truth that institutions and ideologies miss in the practice. Radical interdependence means even our enemies. Even our enemies.

So, the temptation? I’ve known too many who love the people but hate individuals. So, this is important. All ideologies are false gods in waiting. Some ideological stances are important, even desperately important. But they always need the bigger context. And we should never believe we have it right. No one has it all right. We must always be aware that our best interpretations of what’s going on and the fixes they call for are imperfect. They have to be imperfect. They’re thought up by us. You know, people.

However. If we hold our ideologies lightly, if we’re ready to modify or even abandon some precious belief with more complete information, we’re protected from the temptation.

In the Zen tradition much is made of the phrase “not knowing is most intimate.” A dash of uncertainty can be critical to our spiritual lives, and to our actual usefulness in this world.

Finally, Becket’s fourth temptation is to embrace martyrdom as an act of being special. Telling a story where we’re the prophet, the speaker of truth to power. I recall a young colleague once sharing to some of us how he felt there was something he had to tell his congregation, but it was hard. It was prophetic. He fretted, meditated, maybe even prayed a little. Then he did it. And he reported to us that he had, and when he did, the congregation stood and applauded him. An older colleague quietly told him, “You know. If it was prophetic, they wouldn’t have applauded.”

Prophet. Truth teller. In Eliot’s play, to be a saint. With most any introspection, any honest self-reading, we’re almost always going to find each of us is a plaster saint, a plaster prophet, with those clay feet, already cracked, and ready to crumble. If not even with assuming the mantle, breaking apart, collapsing.

Like not knowing, some humility would do most of us a world of good. This is a magic humility. It means letting go of being special whether that special is being good or being bad. Instead, it is a call into our humanity, our ordinariness.

And the wonders that can follow.

Go, go, go, said the bird: human kind

Cannot bear very much reality.

Time past and time future

What might have been and what has been

Point to one end, which is always present.

Amen.

(The image of the murder of Thomas a Becket is from Cassell’s Illustrated History of England, Vol 1, 1865)